لقراءة كتاب، الرجاء تسجيل الدخول إلى حسابك.

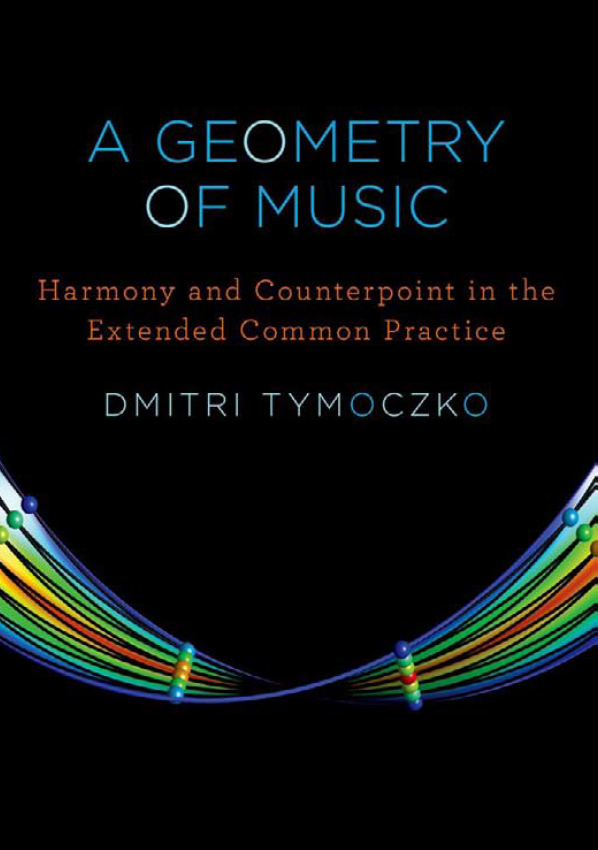

تسجيل الدخولWhen I was about 15 years old, I decided I wanted to be a composer, rather than a

physicist or mathematician. I had recently switched from classical piano to electric

guitar, and although I exhibited no obvious signs of compositional talent, I was fascinated

by the amazing variety of twentieth-century music: the suavely ferocious Rite of

Spring, which made tubas sound cool; the encyclopedic Sgt. Pepper, which contained

multitudes; the hypnotic repetitions of Philip Glass, whose spirit seemed also to infuse

the music of Brian Eno and Robert Fripp; and the geeky sophistication of art rock

and new wave. I was aware of but intimidated by jazz, which seemed to be perpetually

beyond reach, like the gold at the end of a rainbow. (Told by my guitar teacher that

certain chords or scales were jazzy, I would inevitably fi nd that they sounded fl at and

lifeless in my hands.) To a kid growing up in a college town in the 1980s, the musical

world seemed wide open: you could play The Rite of Spring with your rock band, write

symphonies for electric guitars, or do anything else you might imagine.